It’s Tuesday September 23, 2025 and with a little bit of spare time I browse through the helicorder plot of my Raspberry Shake and Boom looking for interesting signals. I find a possible small local earthquake (or more likely a mine blast but I won’t know until I locate it) on the EHZ (vertical ground motion) channel and I find an unusual signal in the infrasound (HDF) channel of station R21C0.

Click or tap on these margin figures to see a larger version.

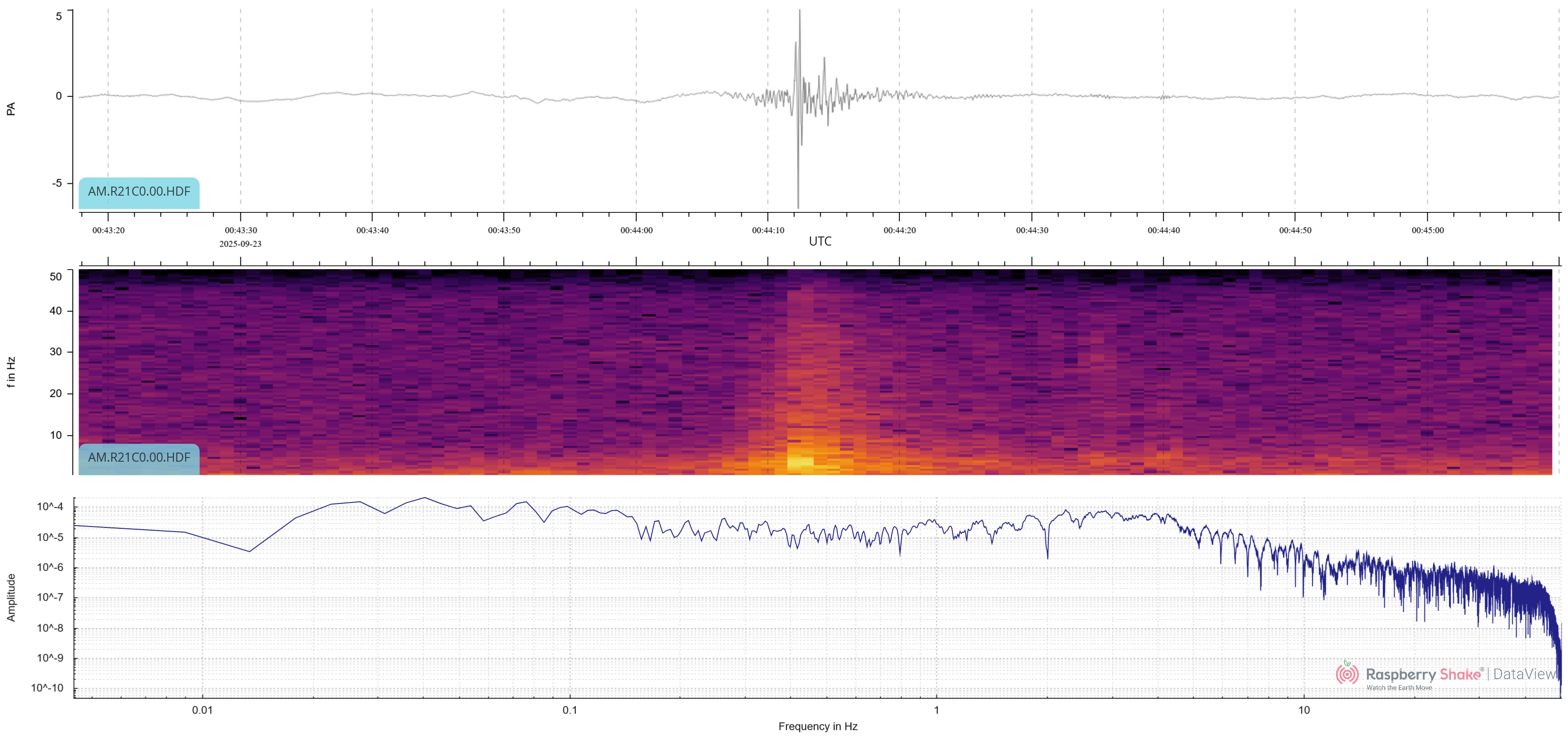

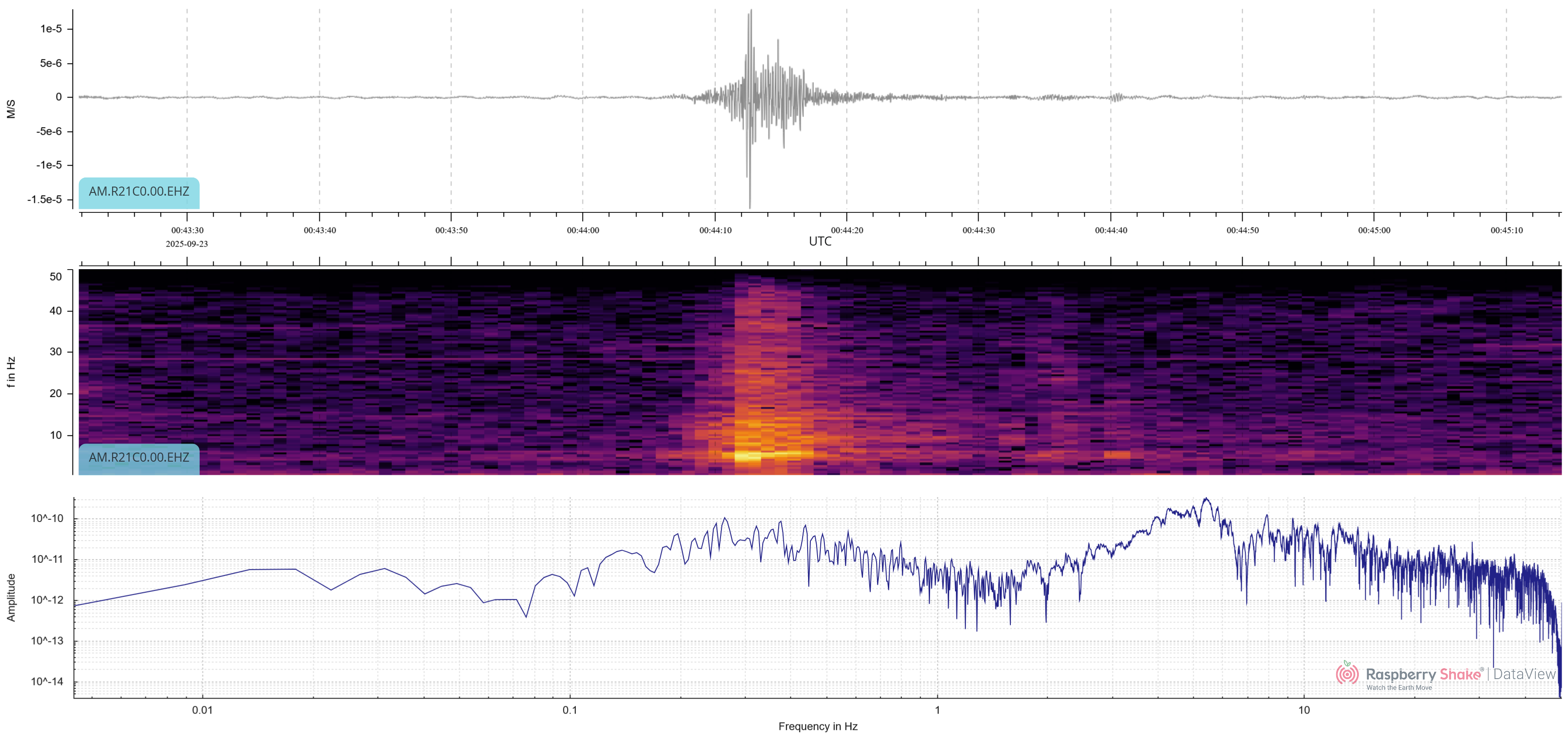

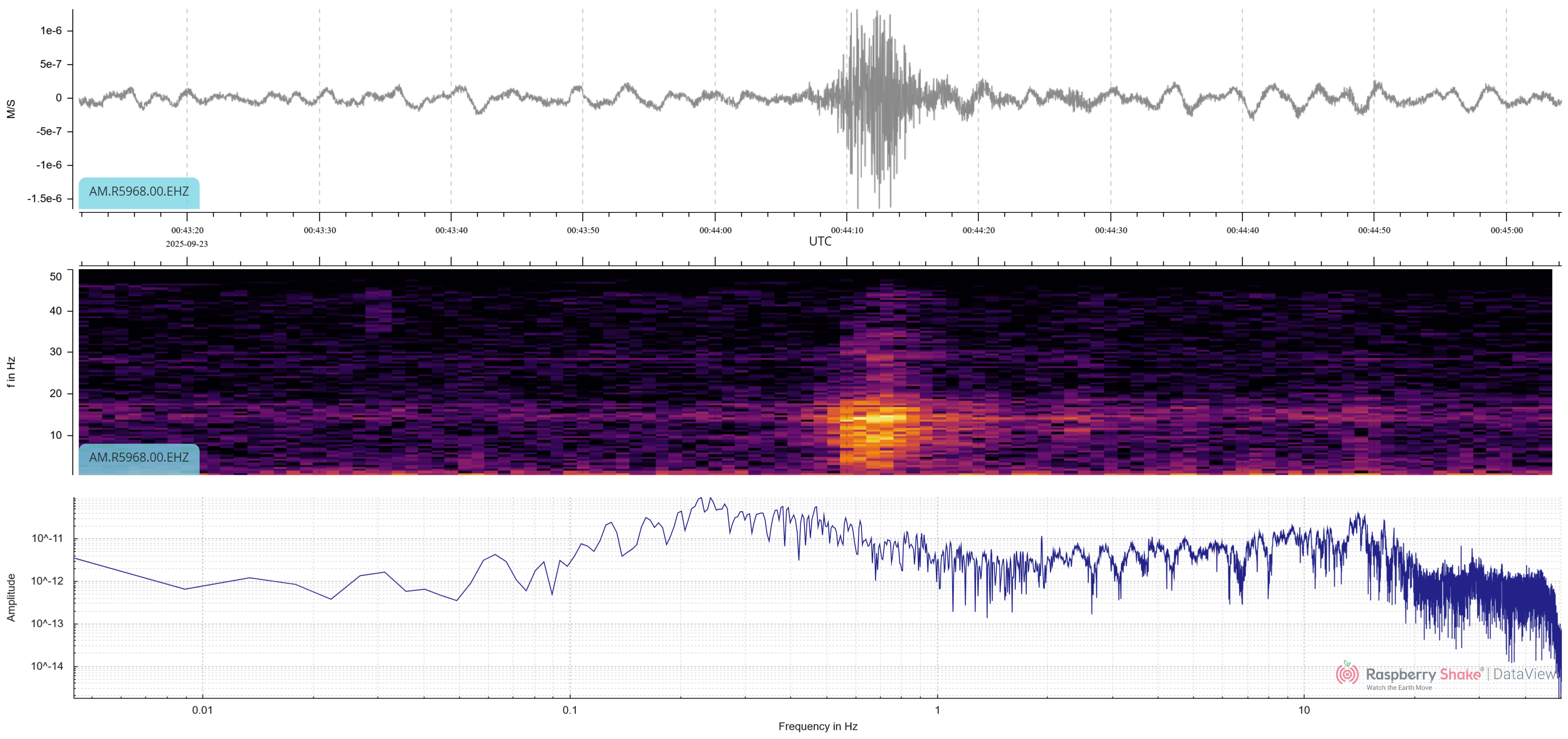

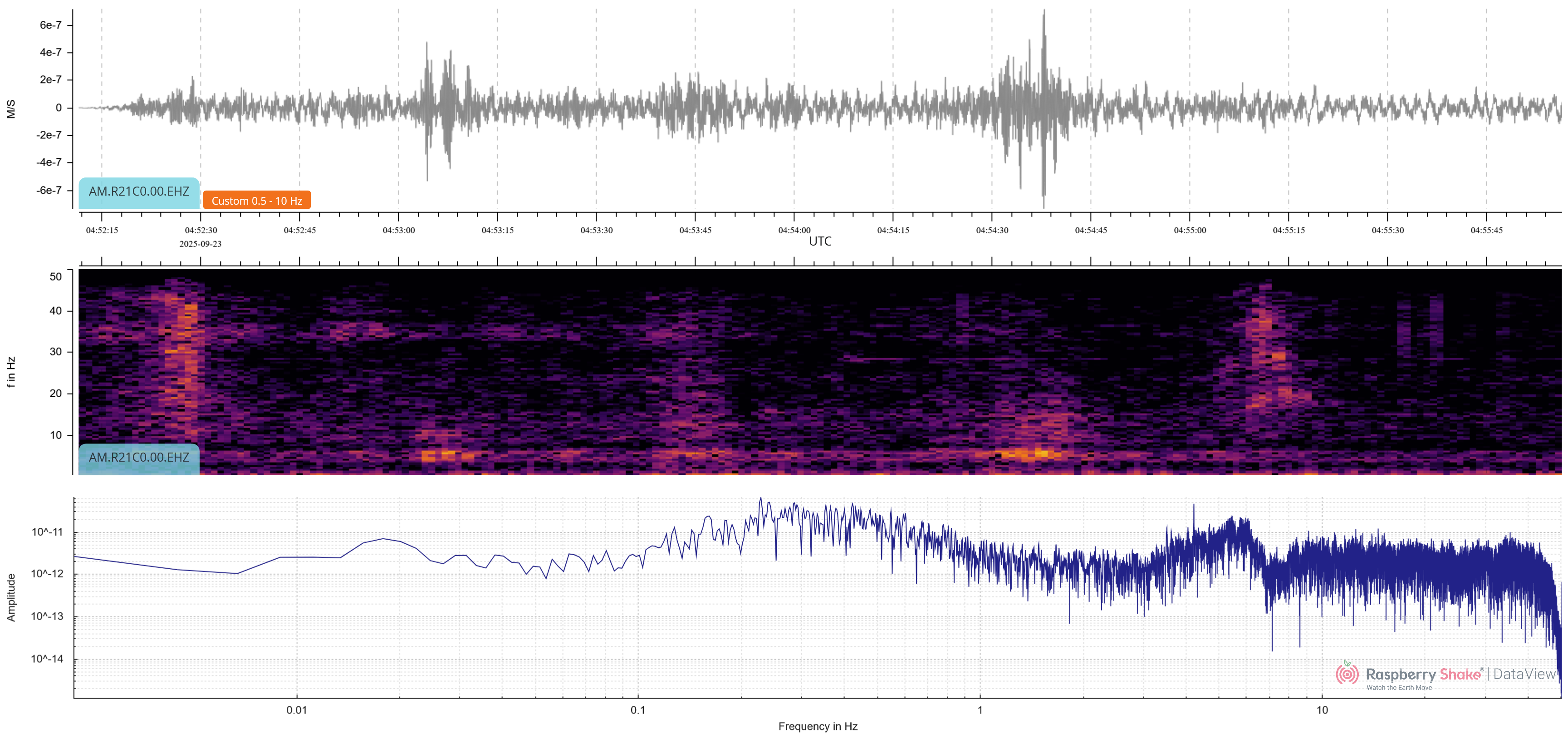

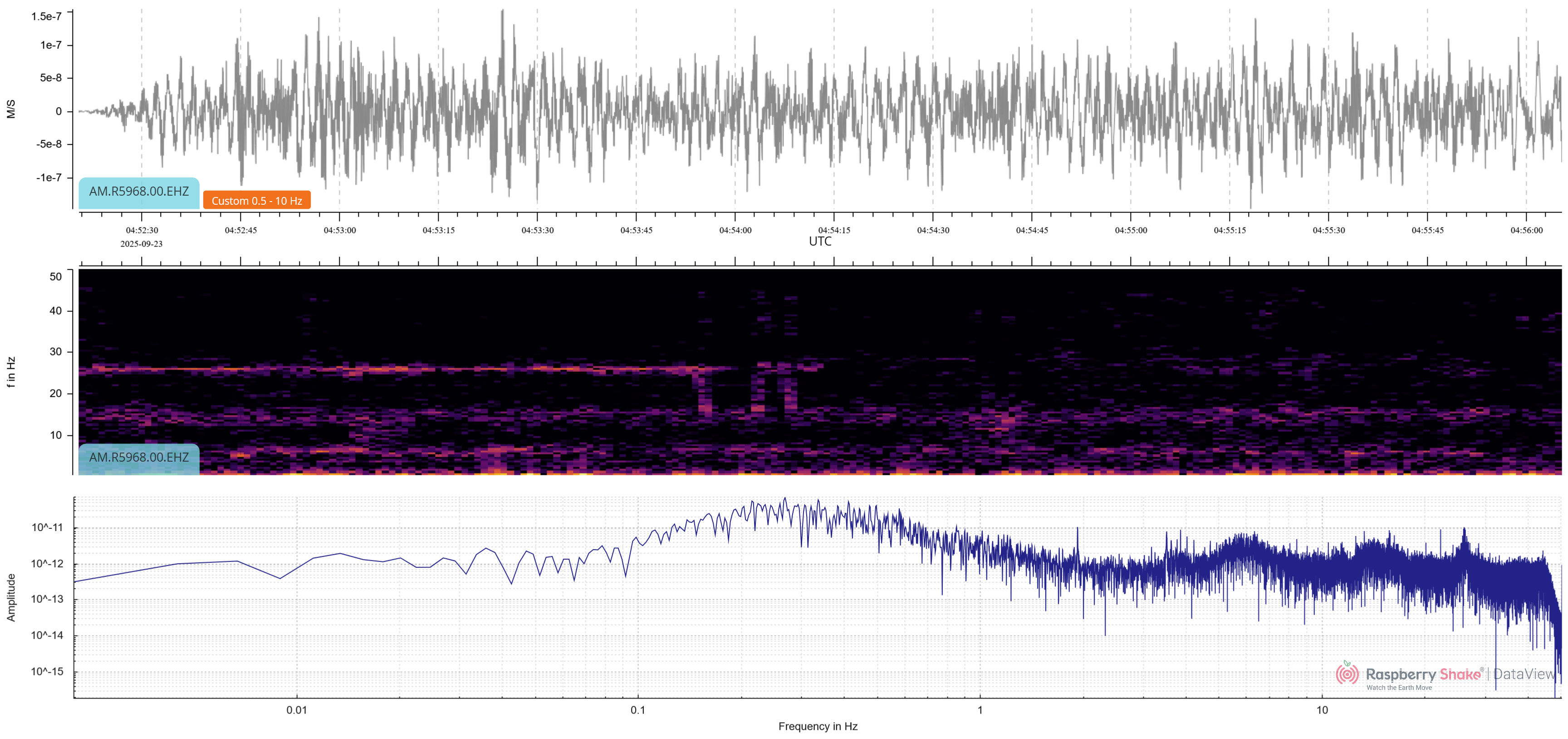

I check on another Oberon Citizen Science Network Raspberry Shake and Boom, station R5968, which is nearby in Chatham Valley, and find the unusual infrasound signal is there on that station as well. In fact, it arrived at R5968 almost simultaneously with its arrival at R21C0 despite the stations being 6 kilometres apart. This either means the signal arrived as a seismic wave that was strong enough to make local infrasound, or it has arrived along a line perpendicular to the line between the two stations. It also means it’s not just local noise. There is a corresponding seismic signal in the EHZ channels of both stations, so either scenario is possible at this stage.

Investigating signals of unknown source can be very time consuming, so I decide process the potential local earthquake first. It ends up being a M2.4 mine blast at the Bulga Open Cut Coal Mine in Bulga, NSW. Most of these that I check are mine blasts but occasionally I’ll find a small local earthquake nowhere near a mine or quarry.

A Stroke of Luck

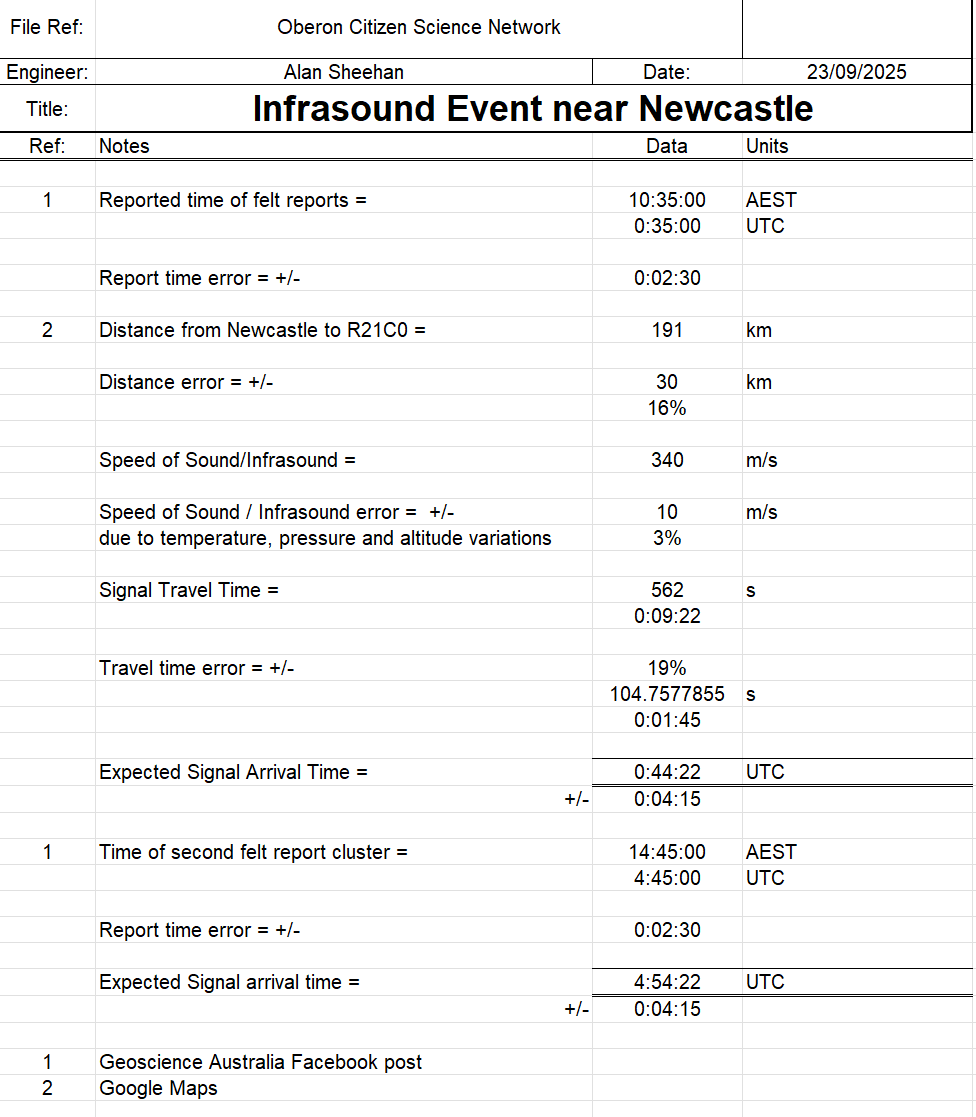

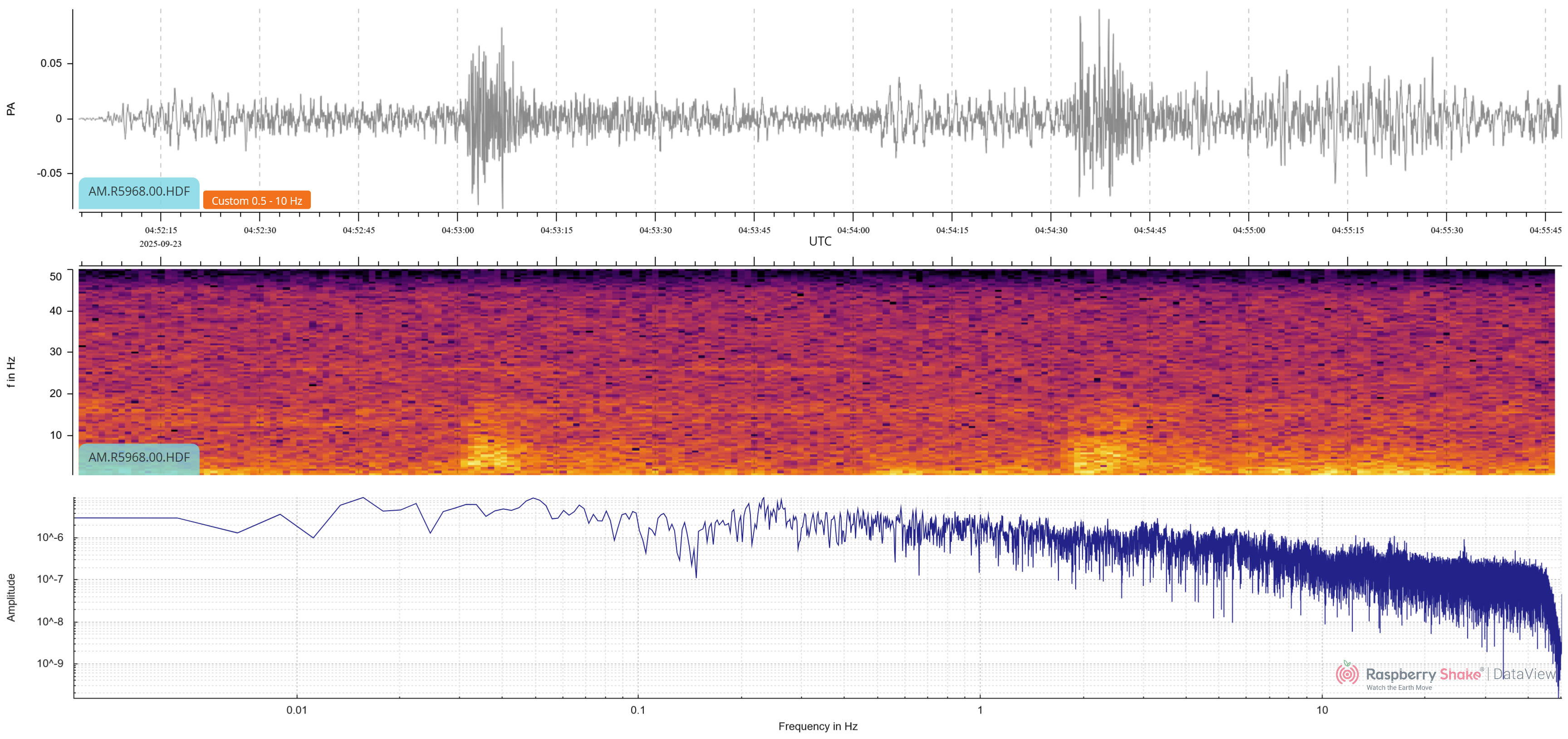

By the time I finish processing the mine blast, Geoscience Australia has posted on social media that many felt reports have been made from the Newcastle area at 10:35am but no seismic activity was found. This is a good sign of an infrasonic event, such as a sonic boom or atmospheric explosion, which is exactly the sort of thing the infrasound channel (HDF) of a Raspberry Shake and Boom is designed to detect.

Calculation of the expected travel time suggests the signal should be near 00:44:22 UTC… and, what do you know… it corresponds with the unusual infrasound signal I’d noted before! The arrival was recorded at about 00:44:10UTC well within the error band for the calculations. This is encouraging - it may simplify identifying the source of the signal. While working out the distance from Newcastle I also check that the path of travel is indeed roughly perpendicular to the line between stations R21C0 and R5968.

Locating the source

I check the next nearest Raspberry Shake and Boom, station S877D at Coonabarabran, but unfortunately there’s no signal detected there. That’s disappointing as at least 3 stations are required to try to pinpoint the source of the signal.

But all is not lost. If the signal is strong enough for the infrasound to generate local ground movement at Oberon, it should do the same at any seismographs closer to the event, so signals should be apparent on other Raspberry Shakes on their EHZ (vertical ground movement) channels.

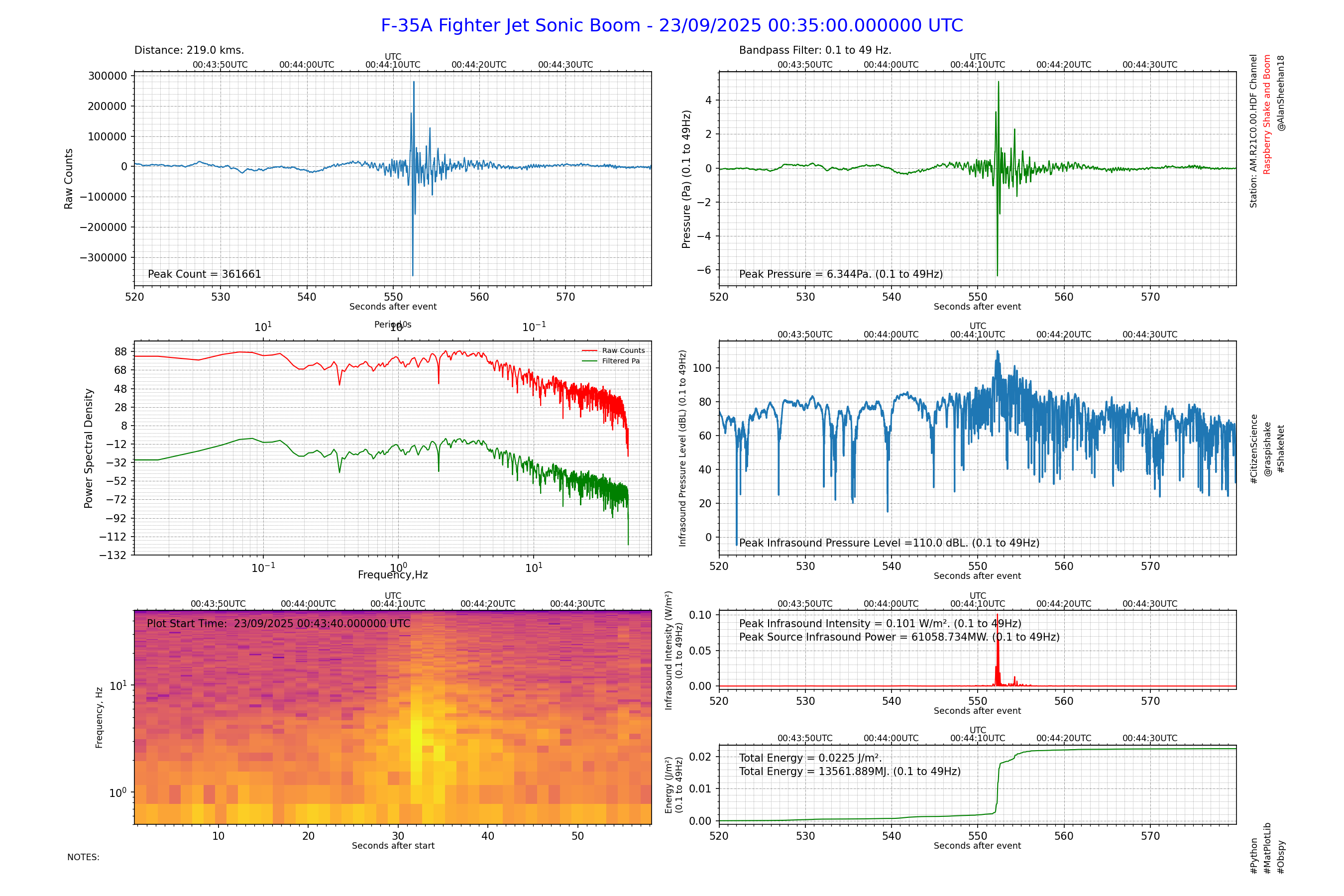

I push my LocalStations.py python script (that I use to local earthquakes and mine blasts) into service, extending the time of the station traces to be long enough to include the infrasound arrivals and look for seismic signals of the infrasound shock wave. Unfortunately only 5 stations record the signals, but that’s enough to locate the event. Through trial and error I locate the source of the signal off the coast of Newcastle. This is an important point, because RAAF aircraft don’t normally fly supersonic unless they are off the coast to avoid damage and annoyance from sonic booms over land.

The RAAF base at Williamtown is home to F-35A Fighter Jets, so it is not unexpected they would be flying off the Newcastle coast. A mate who lives nearby at Port Stephens advised he had heard the boom but didn’t notice the time. He also mentioned the F-35As had been very active all day, and later a social media post confirmed they would be active all week (Sept 20 to 29) as part of preparations for the RAAF Richmond Air Show on September 27 and 28.

Inspection of the helicorder plots on stations R21C0 and R5968 shows there were another 3 similar signals following the initial one. So four sonic booms are likely soon after 10:35am.

By this time, there was another social media post from Geoscience Australia. More felt reports were made in the Newcastle area at 2:45pm the same day and again there was no seismic activity detected. It seemed very likely this would also be a sonic boom.

Applying the same travel times soon located another two likely sonic booms recorded on stations R21C0 and R5968.

Analysis

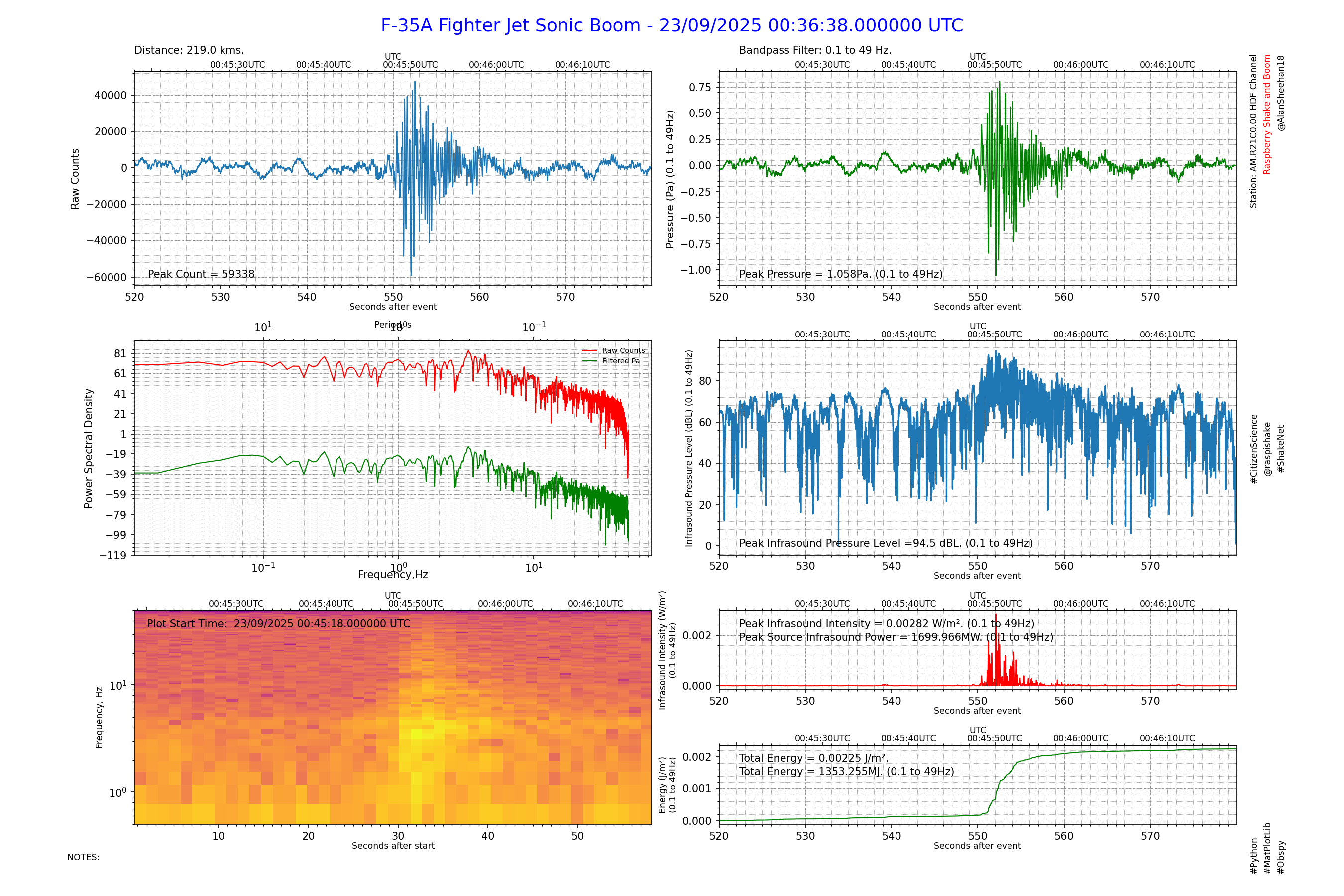

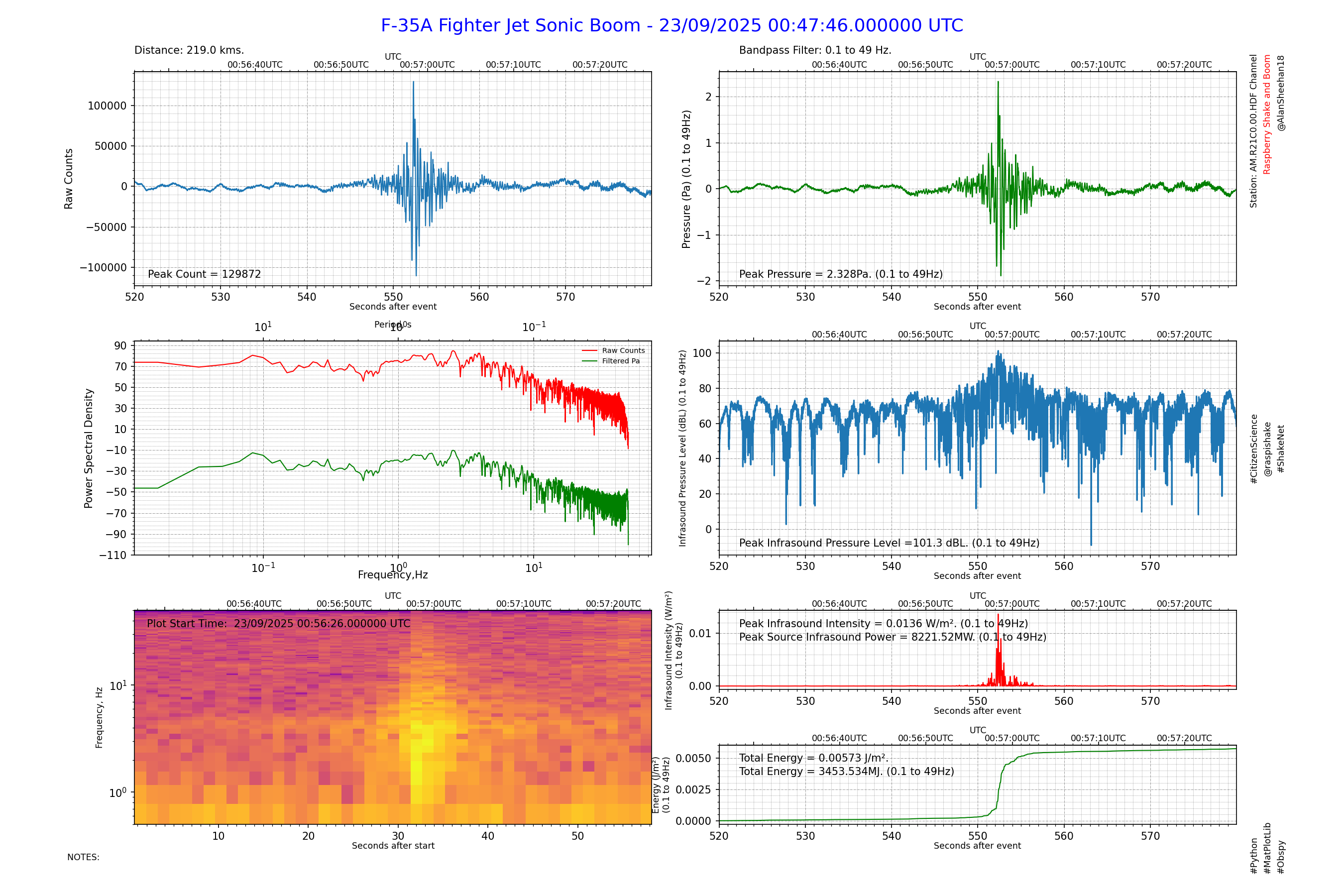

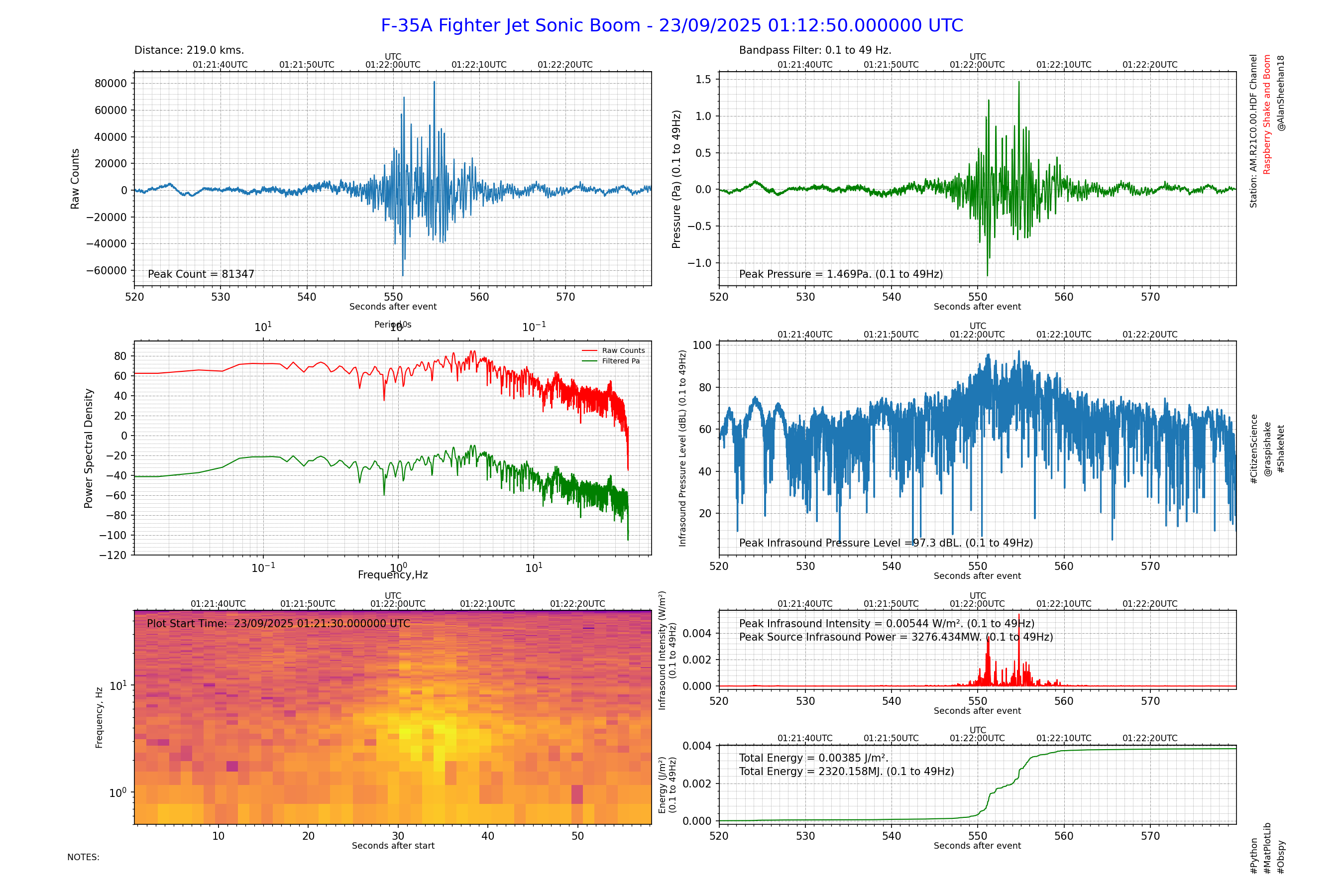

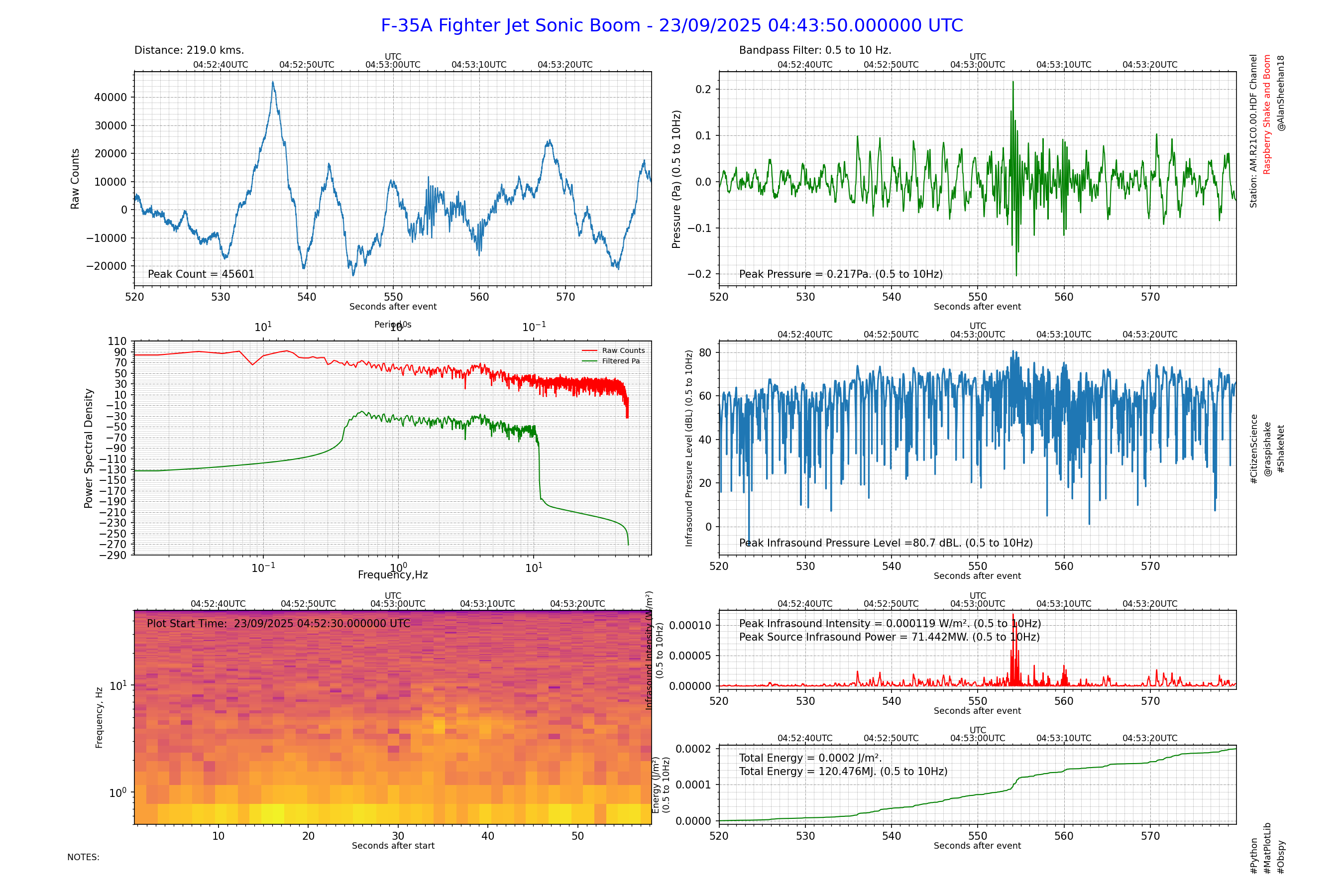

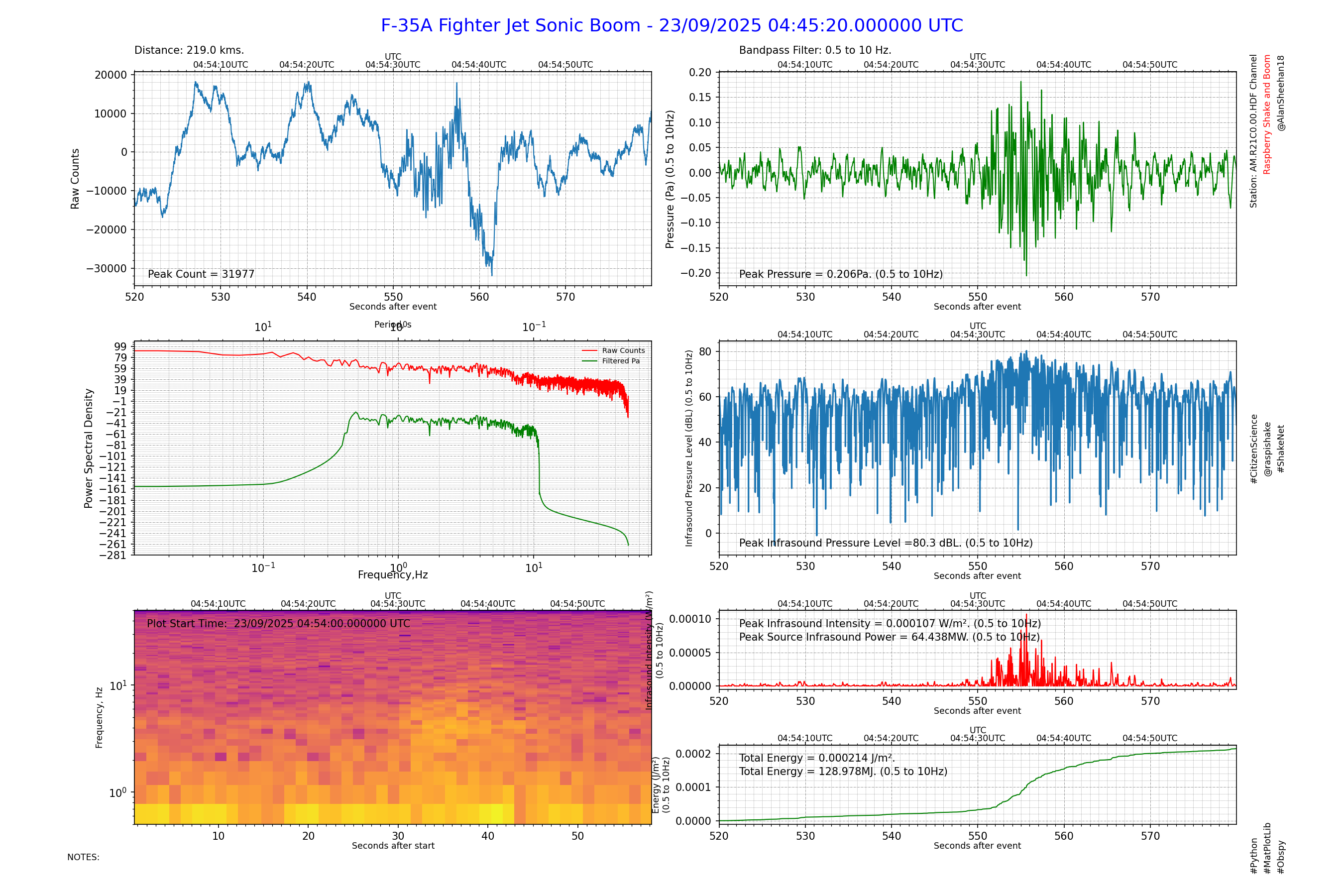

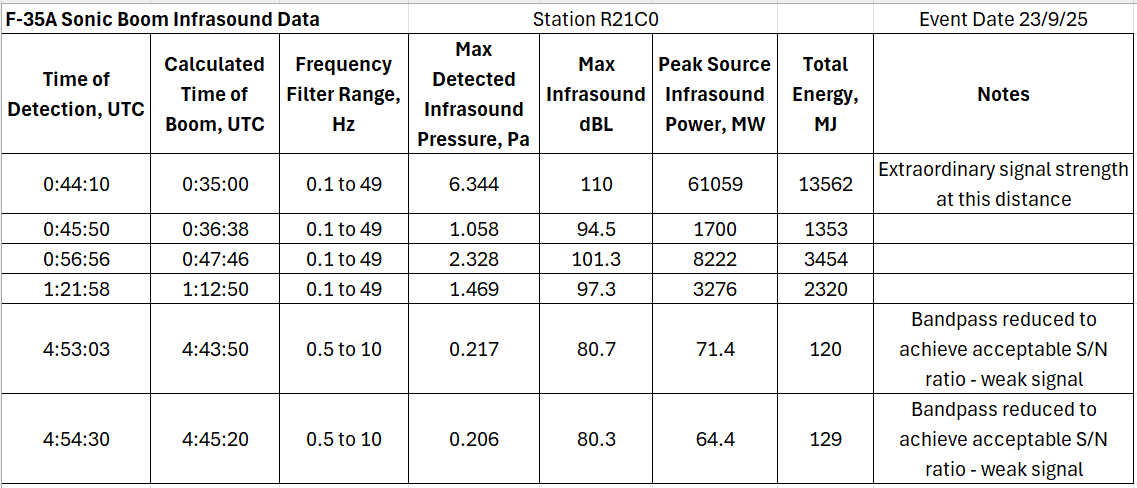

Running the detected signals of the sonic booms through a Boom Report highlights some interesting things - some expected and others not so much.

Click or tap on these margin figures to see a larger version.

The Boom Report is designed to calculate as much information from an infrasound signal as reasonably possible, but when it comes to calculating the Peak Source Infrasound Power and the Total Energy (infrasound) it assumes an omni-directional point source. Sonic Booms are not omni-directional, so the Peak Source Infrasound Power and the Total Energy (infrasound) figures may likely be inflated (they can also be diminished depending on the direction of flight of the aircraft). So not too much can be drawn from these figures.

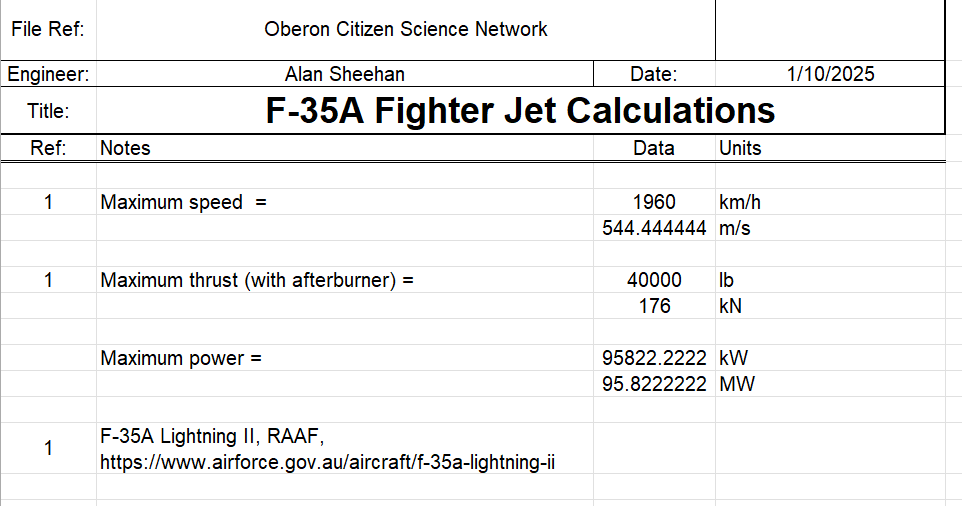

However, the expected source infrasound power for the sonic boom of an aircraft is expected to exceed the power the aircraft can produce. The reason for this involves the non-linearities of compressible flow - the aircraft is constantly using power to maintain pressure wave(s). When detected the pressure waves (sonic boom) release their energy in a very short period of time (high power) compared to the time the aircraft had to fly at supersonic speed to build that pressure wave.

For example, the F-35A fighter power can be calculated as above. About 96MW for maximum power, but it can produce this for a long time in comparison to the duration of a sonic boom.

Another thing that’s very noticable from the summary of data from the sonic booms, is the variability of the data. From a process control point of view the data is extremely variable and the process would be said to be out of control! This really just means there’s lots of things that can affect the measured result.

As mentioned earlier, sonic booms are directional so the intensity of the boom depends on the direction of travel relative to the observer. Other obvious factors are altitude, distance, speed, size of the aircraft, etc.

When it comes to atmospheric conditions, these range from the obvious to obscure in terms of the affect on the tranmission of infrasound. Wind produces infrasound below about 10Hz, so it adds noise that can obscure a signal. Wind also affects the speed that the signal travels across the ground - slower into the wind and faster with the wind. It also affects the direction of sound travelling obliquely to the wind, so it tends to curve sound waves away from the upwind direction and towards the down wind direction. This has the effect of reducing signal intensity upwind and increasing intensity downwind more than expected from the inverse square law.

Temperature and pressure gradients in the atmosphere also tend to bend the sound waves through the air. This is most noticable with sonic booms from aircraft at high altitudes where the boom is heard in a strip beneath the flight path called the “boom carpet” but out side that the boom isn’t heard at all.

And, of course, surface features can reflect and/or absorb sound and infrasound waves affecting the direction and intensity.

It is also noticeable that there is a general trend towards weakening signal strength as the day progressed. The final two detections were so weak, that it was necessary to reduce the bandpass filter width to exclude other infrasound noise to detect the signal. It is likely that this is the result of developing atmospheric conditions on the day: increasing thermals and updrafts over the land causing increasing sea breeze and pressure and temperature gradients developing to bend the signal away from the ground.

All of these factors make infrasound detection over long distances very variable, so sometimes a degree of luck is involved in simply making a detection!

References and Links

Citation

@online{sheehan2025,

author = {Sheehan, Alan},

title = {Infrasonic {Detection} of {Sonic} {Booms}},

date = {2025-09-27},

url = {https://oberon-citizen.science/posts/2025-09-27-Sonic-Boom-Detection/},

langid = {en}

}